RESEARCH AGENDA

My research is at the intersection of race, indigeneity, citizenship, and inequality. Broadly conceived, my research examines how sociopolitical processes, ideologies, and institutions construct, control, and erase populations, peoples, and knowledges. I am particularly interested in how such forces have manifested in settler-colonial states, their impact on persistent inequality, and how marginalized communities are mobilizing resistance movements. My substantive interests are complemented by my methodological strengths in survey methods, applied demography, and in-depth community case studies. I draw on a broad range of theoretical perspectives within sociology, including racial and ethnic identity formation, governmentality, critical race theory, social closure, and state building. My research can be organized into three research strands. The first strand is my dissertation research in which I use the case of Indigenous Peoples to examine how social and political processes of erasure are embedded in settler colonial structures of race, citizenship, and legitimacy; the second strand is my research advancing Indigenous data sovereignty and governance; the third strand is my emerging research program on data for health and economic justice on Indian Reservations. I discuss my research strands and corresponding publications in more detail below.

INDIGENOUS ERASURE

My dissertations, “Data for Sovereignty: Counting and Classifying Tribal Identity” (Demography-University of Waikato) and “Remaking Collective Identities: Data Sovereignty, Citizenship, and Indigenous Nations” (Sociology-University of Arizona) comprise five manuscripts exploring Indigenous erasure through three lenses: statistical erasure, identity erasure, and data erasure.

Statistical Erasure

The first lens I apply in my dissertation research is statistical erasure, which draws on Foucault’s theory of governmentality and political scientist James Scott’s concept of “seeing like a state” to describe how making a population visible to the state is a form of exerting power over the population. I examine how federal statistics systems do this type of legibility work by drawing on social and political ideologies of erasure. American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) populations present an ideal case study to examine such mechanisms because few have endured a more politicized identity formation.

1. My first dissertation manuscript, “Counting and Classifying Native Nations in the United States,” examines the role of the U.S. Census in erasing and reconstructing tribal identities through statistical statecraft. I conduct archival research of census records dating back to the first Census in 1790, which explicitly excluded AIANs. I find that the exclusion of AIANs from the U.S. Census aligns with the peak of the colonial engine in the 18th and 19th centuries informing a deeply flawed colonial narrative of unpopulated land in the west. I build on this historical analysis by showing how the modern era of U.S. Census taking continues the narrative of Indigenous erasure through the racialization of tribal identity starting with the 1970 decennial, which was the first time AIANs were asked for their tribal affiliation as part of the Census race question. My findings suggest that across the last five decennials, conceptual and methodological errors compounded by a lack of meaningful input from Native Nations have resulted in deeply inaccurate, incomplete, and otherwise flawed tribal population data with implications for health, housing, and other federal services that use Census counts to determine funding levels for tribal communities. I anticipate submitting this manuscript for publication by the end of 2019.

Identity Erasure

Second, I look at processes of identity erasure, which straddle theories of racial and ethnic identity formation, social closure, and citizenship.

2. My second dissertation manuscript, “The Blood Line: Colonial Landscapes of Tribal Citizenship Variation,” analyzes how racial logics and state imperatives have distorted AIAN kinship into a measure of blood quantum or a minimum threshold of accepted blood. Using an original database of tribal citizenship criteria that I collected over two years from more than 80 percent of American Indian tribes, I extend Omi and Winant’s racial formation theory to describe blood quantum as a “racial project” wherein the racialization of AIANs has been used to make up the right kind of people (i.e., those with enough blood) to advance the aims of both the settler-colonial state and Native Nations. This manuscript is currently under peer review. I am expanding the conceptual and empirical framework of this article into a book project that compares blood, citizenship, and indigeneity in the U.S., New Zealand, and Mexico. I am particularly committed to inclusion of Central and South American Indigenous peoples in these analyses given the human rights abuses occurring at the U.S.-Mexico border and the stripping of their indigeneity as a mechanism of exclusion.

3. I continue my investigation of identity erasure in my third dissertation manuscript, “Doing Tribal Demography: Population Projections for Indigenous Futures,” a methods piece that examines the relationship between blood quantum and tribal sustainability. Native Nations have the sole authority to confer and abrogate tribal citizenship as sovereign nations. It is their decision to continue using blood quantum metrics at their current levels, increase the threshold, decrease the threshold, or depart from blood quantum all together. Given demographic realities like high rates of intermarriage and urbanization, many Native Nations are facing an impending crisis of tribal sustainability due to strict blood quantum policies. This research is driven by an urgent demand by Native Nations for a tested methodological approach to conduct tribal blood quantum projections. Further, it provides an ideal case to apply my dual disciplinary training in both demography and sociology. I partner with a Native Nation for an in-depth case study to build robust tribal demographic data by a Native Nation for a Native Nation. I present the first detailed analyses comparing U.S. Census tribal data with tribal enrollment data and follow with cohort component population projections looking at hypothetical decreases and increases to blood quantum thresholds for tribal citizenship. I am concluding data analyses and anticipate submitting this manuscript for publication in mid-2020.

Data Erasure

Third, I examine data erasure as a phenomenon of the western gaze that shapes studies of science, technology, and knowledge. I apply this lens to evaluate the glaring data inequities that marginalized populations face across the globe with a particular focus on the state of data dependence in Indigenous communities.

4. My fourth dissertation manuscript, “Building a Data Revolution in Indian Country,” is published in Kukutai and Taylor’s edited volume Indigenous Data Sovereignty: Toward an Agenda (2016). It documents the ancestral origins of American Indian and Alaska Native peoples as data experts, the shift from data sovereignty to data dependence precipitated by colonization, and the growing movement to reclaim Indigenous data sovereignty in the U.S. I document the need for accurate tribal population data by showing how tribes are confronted with hundreds of data sources collected on their populations, yet rarely with or by Indigenous peoples, and further how there’s no tribal statistical data standard in the U.S. unlike in other settler colonial states. I close by identifying the Indigenous data sovereignty movement as way to rebuild tribal data systems and catalyze tribal nation rebuilding.

5. My fifth and final dissertation manuscript, “Data for Native Nation Rebuilding,” explores how Native Nations engage with existing data via official statistics systems and their own tribal data efforts. I combine data from an original survey of 122 tribes with semi-structured interviews of tribal leaders to explore the state resembling activities that tribes are building or need to build to counter official statistics systems. This research was partially conducted in partnership with the National Congress of American Indians, the largest advocacy organization for Native Nations in the U.S. The survey was funded by NSF Grant No. 1439605 as part of the project “Using Science to Build Tribal Capacity for Data-Intensive Research.” I anticipate submitting this manuscript for publication in mid-2020.

INDIGENOUS DATA SOVEREIGNTY AND GOVERNANCE

Native Nations, like other nations , are decision-making entities that need reliable information about their citizens, lands, and resources. However, existing data on tribal populations are often limited to those developed by others—usually federal, state and local governments. For too long, Native Nations have relied on external data sources for tribal decision-making. This dependency is no less a threat to tribal sovereignty than any other legal constraint facing Native Nations.

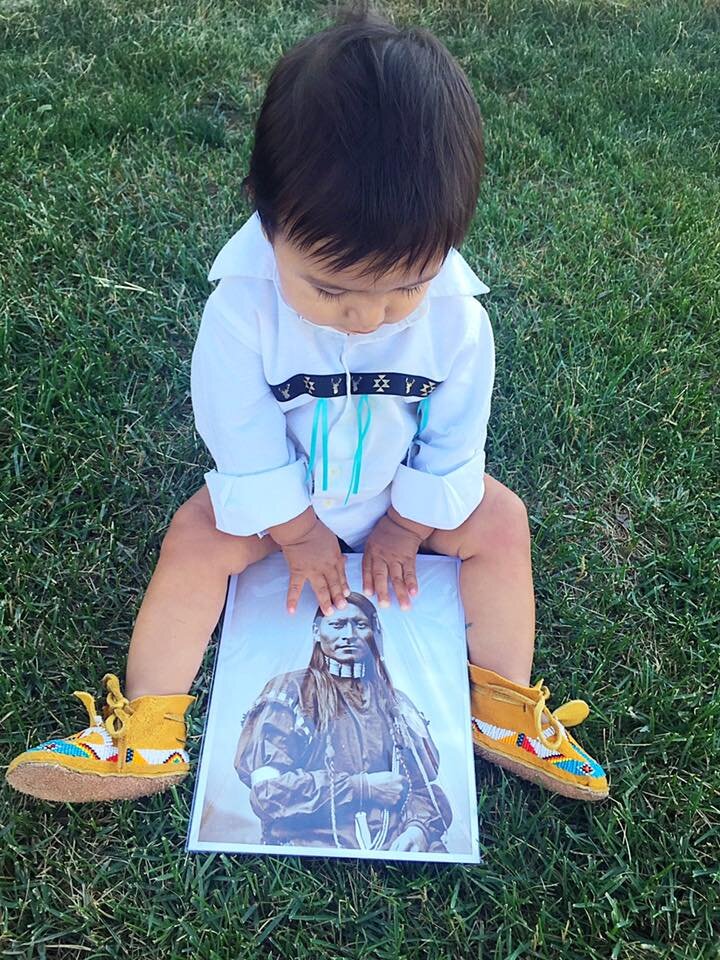

The Indigenous data sovereignty movement is one of reclamation countering colonial narratives of savagery and unsophistication. It acknowledges that Indigenous Peoples have always been data experts with advanced systems of knowledge. Indigenous data sovereignty grounds data within a tribal sovereignty framework. It can be defined as: the right of a nation to govern the collection, ownership, and application of its own data. Indigenous data sovereignty derives from tribes’ inherent right to govern their peoples, lands, and resources.

Indigenous data are perhaps the most valuable tools of self-determination because they drive Indigenous futures. My research to advance Indigenous data sovereignty and governance stems from more than ten years of advocacy and practice in partnership with Native Nations and Indigenous communities in the U.S. and Aotearoa New Zealand. I contribute to a growing domestic and international body of work that supports a two-pronged approach to Indigenous data sovereignty: (1) influencing the better collection and dissemination of external data on Indigenous Peoples, such as census counts and other official statistics, survey, and administrative data; and (2) the development of data systems, practices, and policies by Native Nations for Native Nations.

In 2016, I co-founded the U.S. Indigenous Data Sovereignty Network, which helps ensure that data for and about Native Nations and peoples in the U.S. (American Indians, Alaska Natives, and Native Hawaiians) are utilized to advance Indigenous aspirations for collective and individual wellbeing. I am also a founding member of the Global Indigenous Data Alliance, an international network of Indigenous researchers and practitioners with the collective aim to advance Indigenous control of Indigenous data.

My publication record in this research stream includes numerous reports, policy briefs, op-eds, descriptive statistical summaries, presentations, and other written materials that serve the needs of Native Nations, communities, and other research partners. My “standard” academic publications include:

-

Carroll, Stephanie, Desi Rodriguez-Lonebear, and Andrew Martinez. 2019. “Indigenous Data Governance: Strategies from United States Native Nations.” Data Science Journal, 18(1), p.31. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/dsj-2019-031

-

Walling, Julie, Desi Small-Rodriguez, and Tahu Kukutai. 2009. “Tallying Tribes: Waikato-Tainui in the Census and Iwi Register.” New Zealand Journal of Social Policy (36):2-16.

-

Carroll, Stephanie Russo, Desi Rodriguez-Lonebear, Abigail Echo-Hawk, and Nanibaa’ A. Garrison. “Implications of Indigenous Data Sovereignty for the Governance of Tribal Communities Biomedical Data.” (Under peer review).

-

I am co-editor of an in-process volume for Routledge Press titled Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Policy, which brings together scholars who are leaders within the emerging field of Indigenous data sovereignty and governance. We anticipate publication in late 2020.

-

My book proposal, Surveying Indigenous Communities: Methods and Case Studies, is a methods handbook for engaging in robust and culturally appropriate survey research in partnership with Indigenous communities.

Data for Health and Economic Justice on Indian Reservations

American Indians and Alaska Natives continue to experience some of the highest rates of violent and accidental deaths, chronic disease, barriers to upward mobility like education and employment, and myriad other negative social and economic indicators of wellbeing. One of the most persistent obstacles to addressing these disparities is the lack of accurate, robust, and comprehensive data on American Indian and Alaska Native populations. Building on the last four years as a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health Policy Research Scholar, I am developing an innovative research program committed to data for health and economic justice on Indian Reservations. It has two parts: (1) the relationship between data justice and health equity for Indigenous communities; and (2) how life outcomes are stratified by real and imagined reservation borders. To commence this research, I have two manuscripts in preparation on tribal vital statistics focusing on life expectancy and maternal mortality in tribal populations. I also have active research collaborations exploring administrative data linkage and national survey data for American Indians and Alaska Natives.